PART 5 of 52 ONESHOTS in 52 WEEKS

手塚治虫の『時計仕掛けのりんご』 “Tokeijikake no Ringo” by TEZUKA Osamu

Often described as the “Godfather of Manga” due to his pioneering feats within the medium, Osamu Tezuka remains one of the most influential and successful authors in manga history. Born in 1928, Tezuka was heavily inspired by Disney animations as a young child and quickly began drawing his own comics. He officially debuted in 1946 at the age of 17 with Diary of Ma-chan, a 4-strip cartoon about a mischievous young boy. This was followed the year after by New Treasure Island, a single-volume story loosely based on the Robert Louis Stevenson novel, which propelled Tezuka to the forefront of a new manga craze.

Tezuka produced popular manga throughout his career, with Astro Boy (1952-68), Phoenix (1954-88), Buddha (1972-83), and Black Jack (1973-83) being among his most beloved. Alongside his long-running series, Tezuka also authored many oneshots and short works, which have been collected in various anthologies. One such collection, titled Clockwork Apple, was printed in English in 2021 after a successful crowdfunding campaign by Digital Manga Publishing. It brings together several of Tezuka’s more suspenseful and eerie short stories published between 1968 and 1973, all with a theme of mortality.

Today I’m looking at the collection’s namesake, Clockwork Apple, a 61-page oneshot originally published in Shogakukan’s Weekly Post magazine in 1970. The story is set in the fictional town of Inatake, a settlement surrounded by mountains with a population of around 40,000 people, most of whom become mysteriously lethargic and subservient after eating the local rice.

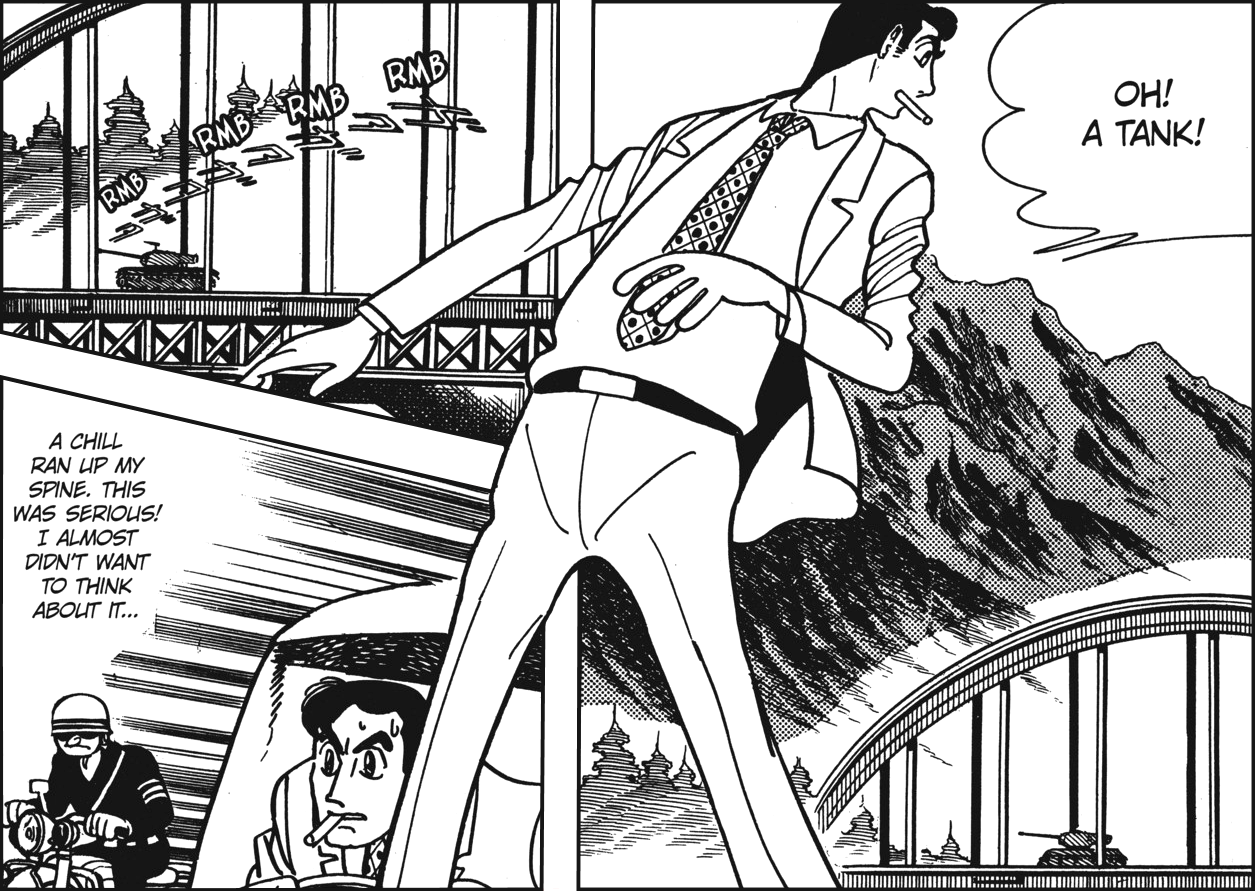

Factory worker Yusaku Shirakawa, who prefers bread to rice, notices his co-workers falling ill after eating lunch from the cafeteria. He takes a sample of rice to be analysed, which is found to contain a memory-altering drug. At the same time, Inatake loses contact with the rest of Japan, with the daily newspaper reporting the collapse of a key bridge leading in and out of the town. As one of the few townspeople still in his right mind, Yusaku takes it upon himself to investigate. Curiously, he finds the bridge still intact, but notices the military mobilising nearby. Beginning to draw too much attention, Yusaku soon find that he’s under surveillance, and is quickly embroiled in the makings of a coup, where an enigmatic rebel leader plans to secretly subdue and take over the town.

Osamu Tezuka uses several real-life references, including the geography of Japan, historical coup d’état’s in the 1930s, and his knowledge of medicine as a medical graduate, to stage a piece of speculative fiction you can quickly get on board with. His story plays as a “what if” scenario, re-framing a chilling part of history within a more modern context, casting an eye on what the author describes as the “insanity of man.” It unravels with great intrigue, as everyman Yusaku finds himself in the midst of an insidious and history defining plot.

However, the ending comes with a little less tact. It’s as though author Tezuka was having much fun composing the story, until he realised he had hit the page limit and needed to wrap it up. Abruptly it ends, and with a convenient act of God, but this isn’t the most distracting turn in the plot. Earlier in the story, when thinking about how to send for help, Yusaku devises a plan to write SOS messages on the bellies of 200 fish and have them swim down river. It is so goofy that it’s wildly enjoyable, but the suspenseful tone of the piece is impaired by such bizarre aspects.

Still, the story proves to be a fascinating and thought-provoking tale whose relevance hasn’t wavered. What’s more, the artwork is stunning. Tezuka’s characters are more cartoonish in design than what you’ll typically see in contemporary manga, but he’s an expert in expression, conveying emotions and physiology with keen precision. He employs detailed hatching techniques, illustrating light and shadow with dramatic effect, and painstakingly details even the edges of the frame. There is little blank space in most panels, with impressive background spreads, displaying nature—mountains, trees, rivers—and infrastructure. There’s yet more expertise in his panel arrangement, with all manner of creative layouts, which help to produce a dynamic and exciting flow. Even the sound effects aren’t exempt from some flourish. During a stormy scene, Tezuka illustrates the sound effect of a lightning strike in 3D, which results in a particularly vivid and impressive panel.

The cartoony aspect of Osamu Tezuka’s characters can, at a glance, mask the astounding detail in his work, but when you stop to look, there is so much to enjoy. Despite some shortcomings, there’s a lot of greatness not only in Clockwork Apple, but the entirety of the collection, which has left me excited to read much more short work by the great Tezuka.

Click here to explore the rest of 52 Oneshots in 52 Weeks and find my numerical ratings on MyAnimeList!