“At its heart Gintama is a science fiction human pseudo-historical comedy. The bottom line is that this is a nonsense manga. But I don’t believe in telling readers what to think, so read it any way you like.” – Hideaki Sorachi

Set during the 19th century in an alternate-reality Edo that has been conquered by aliens, Gintama follows redundant samurai Sakata Gintoki, who struggles to make ends meet working as a jack of all trades in a world that has left him behind. One of the most quirky series in a sea of eccentricity, Gintama is a fantastically creative work and as consistent, comical and compelling now as it was a decade ago.

The story is told in a largely episodic fashion, with each chapter presenting a self-contained story featuring a handful of the cast. These chapters are largely comedic, but do well to avoid repetition — even after over sixty volumes — thanks to the fantastical, ever-expanding setting and the authors innate talent for comedy writing.

But alongside the ingenious gags and multifarious humour, Sorachi tinkers with a number of story arcs that are occasionally tonally opposite to the stand-alone chapters, presenting a more serious side to the characters and exploring more brooding and dramatic topics.

The shift from comedy to drama can be somewhat jarring at first, but ultimately adds an interesting, alternate edge to the series and allows for greater character development and expanded narrative that is simply not possible in the episodic adventures and which is often absent in comedy manga. It’s an aspect that allows Gintama to stand out among its peers, though the arcs themselves are typically shōnen and never quite leave the boundaries of the genre.

Another element that keeps Gintama invigorated is the sheer number of characters. The main trio are — of course — featured the most, but Sorachi is especially good at utilising the supporting cast, which expands with every volume. The cast are very much comedy archetypes, with Sorachi playing on this a lot, often breaking the fourth wall and self-referencing (himself a character in his own manga, portrayed as a lazy ape), but archetypal characters never prevent the author from being innovative and unorthodox. It’s clear Sorachi has a lot of fun writing Gintama; he allows his imagination to run wild and frequently experiments with the components of his work, playing with plot devices and preconceived notions in order to conjure inventive and unconventional ways to entertain the reader. Sorachi wholeheartedly embraces his bizarre and outlandish creation, pushing his archetypes in unexpected and outrageous directions.

The comedy itself is wonderfully varied, ranging from traditional Japanese slapstick and manzai style sketches, to satire, parody and meticulously plotted witticism. Sorachi’s use of parodic elements and the series’ dynamic setting also allow the author to explore a variety of genres, from hardboiled detective stories to steampunk and high fantasy, creating a delectable blend of homages and whimsical imitations, all the while creating some amusing pastiches of popular culture, both Japanese and Western.

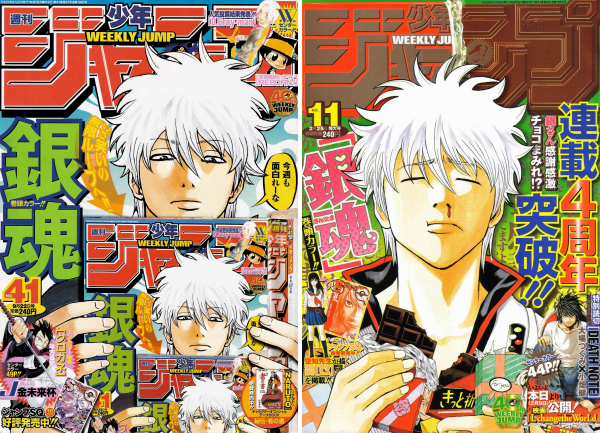

Sorachi revealed in one of Gintama’s many afterwords that he was interested in becoming a mangaka as a child, but abandoned his dream after showing his artwork to his father, who laughed at it. However, after trying his hand at manga again following college, he eventually found his feet with Gintama — despite a tremulous first year — and is now published weekly in Shueisha’s famous Shōnen Jump magazine. Understandably, his artwork has gone from strength to strength after decades of practice, with the manga now boasting a very polished, distinctive style.

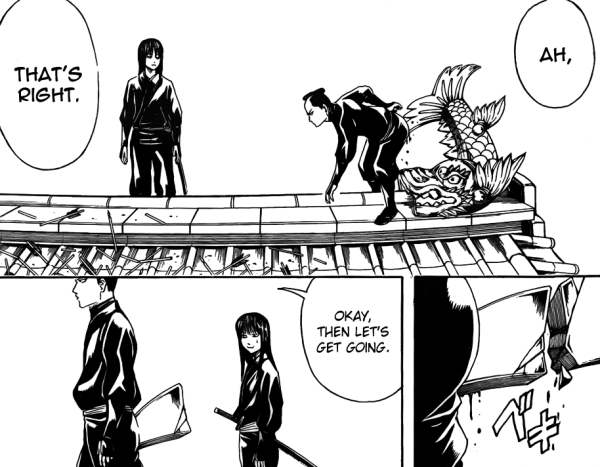

Gintama features a heavy use of line work and inking over a more sketchy approach, with Sorachi utilising a large number of panels for the comedic segments which feature a lot of dialogue and fast paced quips. He tends to reserve full-page artwork and double page spreads chiefly for action scenes and — during the dramatic story arcs — allows the characters more room and places larger emphasis on the backgrounds and surroundings to create detailed set-pieces. Sorachi’s character designs are a particular stand-out element, with the setting offering a lot of freedom to create some very unconventional and peculiar creatures.

With an inventiveness, imagination and originality rarely matched in its genre, Hideaki Sorachi’s Gintama is at the very forefront of comedy manga. It’s an offbeat marriage of genres and themes seldom thought to coincide, but the author makes it work with his eloquent blend of playful storytelling, wondrous imagination and razor sharp wit. A tremendous achievement, through and through.