Pioneered by artists such as Osamu Tezuka and Machiko Hasegawa, modern manga has a history dating back almost eighty years. A recognisable style has formed over the decades, with notable techniques both across and within each demographic, but the medium is never short on creativity, with artists continually experimenting and innovating with distinctive methodology.

With a goal of highlighting mangaka that are somewhat atypical in their approach, below you’ll find five series with distinct and impressive art styles, detailed with a synopsis and brief analysis, alongside two image examples that you can swipe between using the cursor in the middle.

You can find more manga content across my blog, including a year-long project analysing and discussing over fifty oneshots. You can also connect with me on MyAnimeList!

——————–

Takemitsu Zamurai by Taiyo Matsumoto & Issei Eifuku

竹光侍 「Takemitsuzamurai」 Published in Big Comic Spirits (2006 – 2010)

Masterless samurai Souichirou Senou arrives in Edo, planning to hang up his sword and settle in the city. At first, he is met with suspicion from local residents, but Senou’s childlike wonder and helpful persona quickly win them around. However, this new peaceful existence is shattered when Senou is drawn back into conflict, with each skirmish slowly reawakening the beastly bloodlust of his past.

Taiyo Matsumoto is a mangaka known for his idiosyncratic style, illustrating with bold lines and liberal inking in his early series. In Takemitsu Zamurai, the artist puts a spin on his defined style, swapping traditional manga techniques for thick brushstrokes and inky watercolours. Through an expert combination of striking detail and composition, the artist illustrates action with a frenetic energy uniquely his own, crafting ferocious set pieces with exquisitely layered strokes. Opposite this, in the more idyllic scenarios between action, Matsumoto’s pen mimics the fine detail of woodblock prints, pairing deftly with the manga’s historical setting. The lovable Senou is often illustrated with an almost cartoonish design, with distorted eyes and a simple line for a mouth, charmingly juxtaposed to his barbaric demeanour that is unleashed in combat.

——————–

Dorohedoro by Q Hayashida

ドロヘドロ 「Dorohedoro」Published in Monthly Shōnen Sunday (2000 – 2018)

Caiman is a well-built man who, from the shoulders up, has the appearance of a lizard. Unique even within a world of strange creatures, the reason for Caiman’s distinctive appearance eludes him, with a past shrouded in mystery. Living among the lowest dregs of society, in a decrepit hellscape known as the Hole, Caiman and his female companion Nikaido hunt down magic-users, the upper-class members of the commune, hoping to find answers to Caiman’s reptilian features.

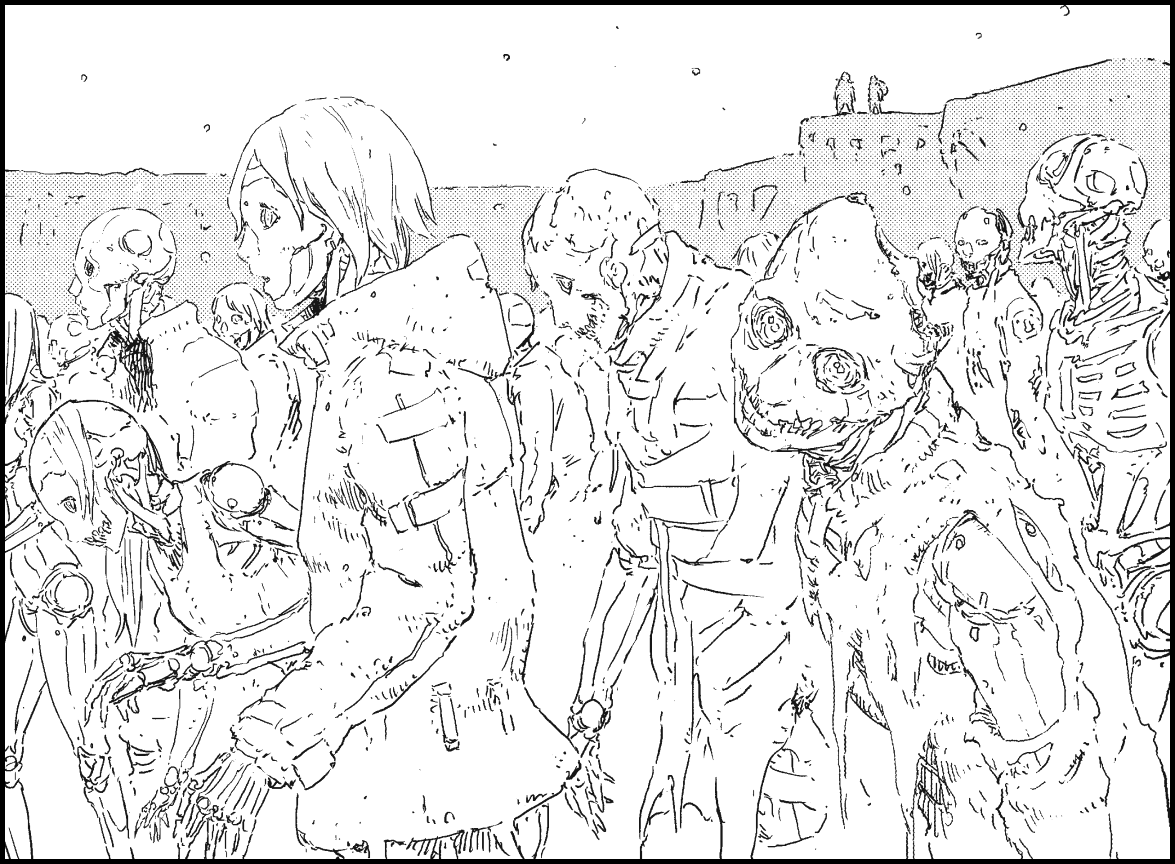

Q Hayashida’s artwork is brought to life through minute detail. Its sewery setting is full of character, with crude environments made vibrant and bustling through an equal focus on background and foreground. The author’s free-flowing style can lead to some odd character perspectives, but the backdrops, rich in all manner of dirt, scratches, scuffs, spills, rubble, dents, waste and whatnot, produce a remarkable level of intricacy, drawing the readers’ eyes to every nook and cranny of the page. The artist’s gritty craftsmanship lends itself well to bizarre creature designs and thrilling skirmishes, where characters’ distinctive abilities are realised through a noisy but ever-creative visual flair. However, what really sets Hayashida apart from most other mangaka is her determination to work alone, without the aid of any assistants. Every penstroke her own, Dorohedoro is surely one of the most detailed solo ventures by any manga artist, told through 167 chapters drawn over 18 years.

——————–

Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms by Fumiyo Kono

夕凪の街 桜の国 「Yūnagi no Machi, Sakura no Kuni」Published in Weekly Manga Action (2003 – 2004)

Told across two interconnected stories, Fumiyo Kono’s manga explores the effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on ordinary townsfolk. The first, Town of Evening Calm, is set ten years after the bombing, with protagonist Minami struggling to come to terms with her survival, where she must forge a future amidst the shadow of the bomb. The second, Country of Cherry Blossoms, follows Minami’s niece decades later, exploring the bombing’s aftermath on a new generation of children and young adults.

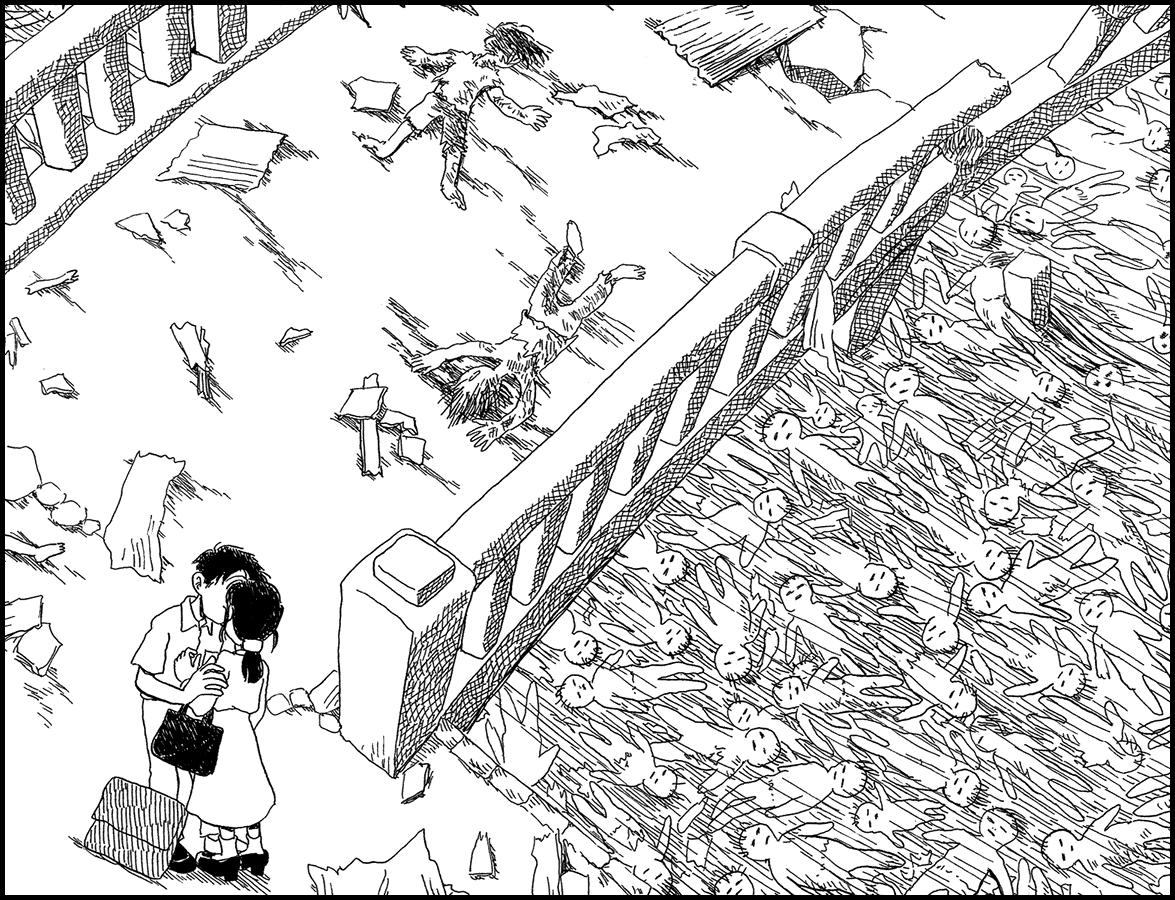

Fumiyo Kono excels in her linework, creating impressive spreads filled to the edges with precise detail, utilising crosshatching techniques for shading in favour of inking. From a multitude of chevrons and lines, she composes gorgeous vistas whose delicacy and ease almost masks their astonishing precision and depth. Kono’s characters, with their big cheeks, round faces and slight demeanours, are a touch chibi-esque, composed with a tender quality that matches poignantly with the story’s pensive reflections. In a stand-out page, Kono illustrates Hiroshima’s Genbaku Dome, backlit by the sun, casting evocative shadows through its many holes and windows. Her artwork is astoundingly expressive in its soft, ruminative quality. The artist displays her expertise further in the cover and contents pages, swapping her lined detail for stunning watercolour panoramas.

——————–

Gantz by Hiroya Oku

ガンツ 「Gantsu」 Published in Weekly Young Jump (2000 – 2013)

While waiting for the train one morning, high school acquaintances Kei Kurono and Masaru Kato are spurred into action as a drunken man falls onto the tracks. They succeed in rescuing the man, but are themselves killed by the approaching train. The two suddenly awaken in an apartment room with other recently deceased strangers, who are all instructed by an ominous black orb positioned on the floor to hunt down and kill an alien-like creature, setting in motion a deadly game of survival. All who succeed at their mission can return to their daily lives, until they are uprooted again by the orb and pitted against another foe.

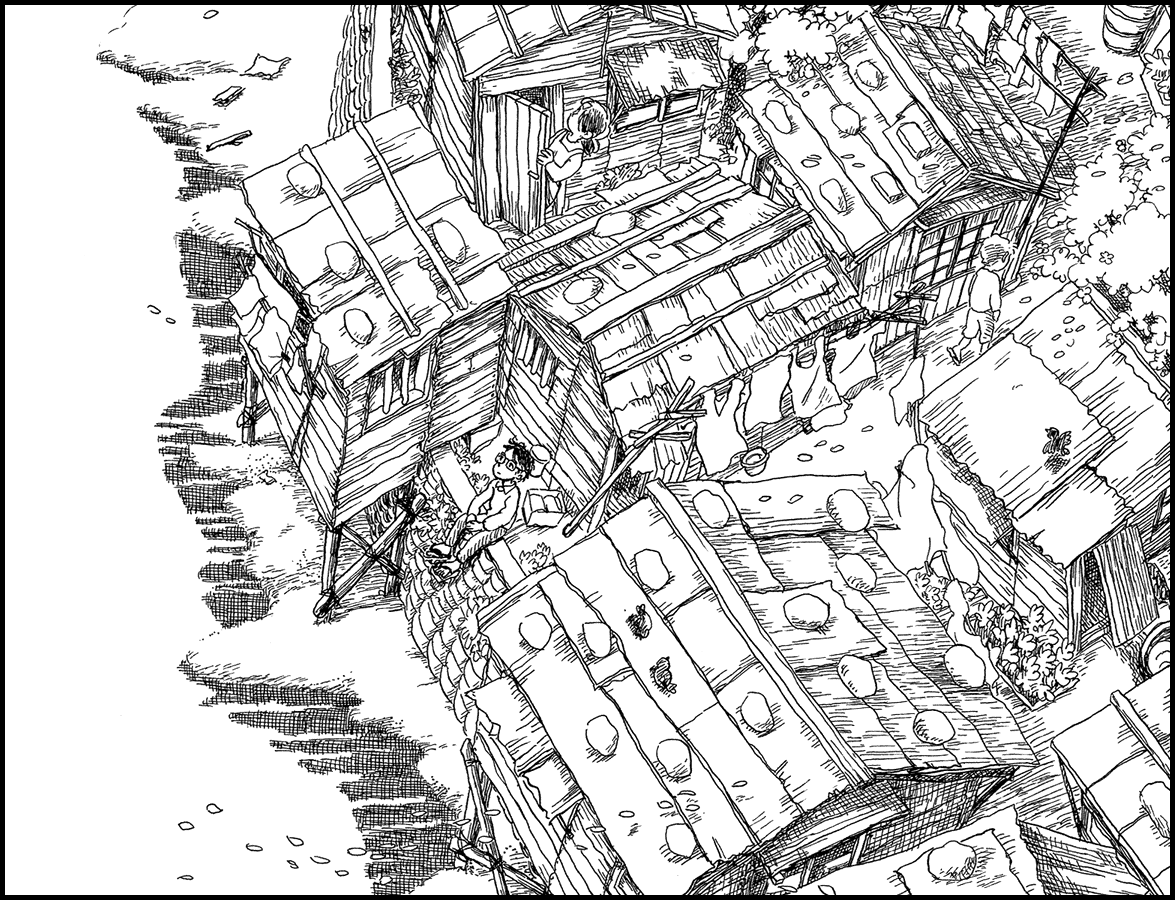

Hiroya Oku crafts a unique style in his series through a combination of digital and analogue art, making use of programs such as Poser, alongside Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. Working from a storyboard, the artist begins composing each page using a computer — he digitally creates 3D models, allowing him to freely alter the poses, positions and angles of his characters. After placing his character models, Oku and his assistants then render backgrounds and other 3D objects to implement as needed. He prints the page out and uses it to trace the compiled elements, slowly putting together a more typical manga portrait drawn in pen, scanning and printing it several times over as detail is added. The end result is sometimes a little crude, with awkward perspectives and layering, but at its best, the technique produces artwork with striking depth and staggering detail, often with an impactful sense of scale.

——————–

Aposimz by Tsutomu Nihei

人形の国 「Ningyō no Kuni」Published in Monthly Shōnen Sirius (2017 – 2021)

The surface dwellers of an artificial planet named Aposimz eke out an arduous existence, battling not only a freezing environment and aggressive natives who live underground, but also a quick-spreading disease which transforms normal humans into biomechanical creatures. A solace is found in certain humans who are mutated into ‘Regular Frames’ — biologically immortal beings with heightened resilience and strength, who are looked to and revered by regular humans as protectors able to forge them toward a brighter future.

Tsutomu Nihei is well known for his meticulous artwork, utilising his background in construction and architecture to create imposing settings with fascinating structural designs, which are often strewn in winding mechanical components. These environments are darkly crafted through a liberal use of inking and screentone, with the author often skipping dialogue in early series to rely solely on visual storytelling and atmosphere. In Aposimz, he swaps his usual bleak darkness for a bleak whiteness, forming a wintry world through extremely conservative employment of any black space, where the absence of tone is the very detail. Emulating a hopeless snow blind effect, the author fashions desolate landscapes and stark interiors which are nightmarish in their lucid austerity. Despite being decidedly minimalist compared to Nihei’s other work, Aposimz wholly exhibits the author’s talent for composing dramatic settings and compelling technical designs.

Do you have any preference regarding the first half of Nihei’s career vs the second half? Do any particular works of his stand out as your favorite?

LikeLiked by 2 people

BLAME! is my favourite. I love the sombre atmosphere and imposing settings, which Nihei renders beautifully in an exceptionally gritty and nebulous fashion. Abara and Biomega continue in a similar vein, before he adopted a more refined style with Knights of Sidonia. I didn’t get into the latter much, but I know a lot of people are very fond of it. I’m reading through Aposimz now and am enjoying it a lot. I think it’s very effective and unique in its presentation, however Nihei’s early work is far and away his best in my opinion! But all of his series seem to exist in a rather vague shared universe which is interesting. Do you have a favourite?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I own BLAME, Abara, and Biomega and reread them every few years, but have never really given the post-Biomega stuff a fair shake. That’s why I was asking actually — I adore that earlier stuff and sometimes I feel like I should read Knights of Sidonia or something like that, so I was wondering what your opinion was. I don’t read much manga these days so I tend to just stick to rereading from my old library.

I don’t know if you’ve read this, but I think maybe his being a little dismissive of those BLAME years has soured me on the new stuff: https://mangabrog.wordpress.com/2016/02/29/a-2016-interview-with-tsutomu-nihei/

I reread Abara a couple of months ago and the main thing that struck me was how much of its DNA has been absorbed into Chainsaw Man. It’s sort of a failed project in that the second volume feels rushed in a way that you can’t just chalk up to Nihei being weird; the art quality drops around the same time and you can see that clearly SOMETHING happened. But even in that sort of incomplete state it’s SO impressive, especially that first volume, that it must have really stuck with Fujimoto (among other artists) — the fight with the bomb devil, specifically, feels like he’s just straight-forwardly doing a gauna. And it was just nice to think that this semi-aborted two-volume thing kind of went on to contribute to this massive hit, and it’ll sort of live on in that way.

Anyway, I usually like it when artists try to reinvent their art style mid-career (like Matsumoto Taiyo has done repeatedly, for example), so I probably should pick up one of Nihei’s new post-grunge works, although I’m not sure which one to go for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Knights of Sidonia is probably his manga I’m least familiar with, though I did watch half of the anime. My impression of it is that it’s probably one of his most accessible works for a more casual audience. Not that it isn’t challenging or esoteric, but it certainly seemed to bridge the gap toward a more mainstream work for Nihei, notably in the characters. Still, it’s his second highest rated series on both MAL and Manga Updates, outranked only by BLAME, so perhaps there is something special to it. Now I’m curious to give it another go after Aposimz.

Thanks for linking that interview! I have a vague memory of it — perhaps I read it a long time ago. That’s probably where I got the notion he was going for mass appeal with Sidonia, since he says as much. Interesting that he was even considering changing his pen name. He certainly seems to have distanced himself quite drastically from his early style.

The bomb devil was one of my favourite arcs in Chainsaw Man, and I know Tatsuki Fujimoto has explicitly stated Abara as an influence, but I didn’t make that connection before. You detailed it eloquently! It’s always fascinating seeing manga overlap and given new life in later series as influences and homages. Recently, I really loved Inio Asano’s creative spin on Doraemon in his manga Dead Dead Demon’s Dededede Destruction.

Matsumoto is such an exciting innovator. Sometimes I miss the energy and vividness of a series like Ping Pong, but equally his painterly style in more recent manga like Sunny and Cats of the Louvre is just as spellbinding, despite being almost antithetical in ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, as much as I LOVE the way he drew Sunny and the like, I do sort of wonder what it’d look like now if he tried to go back to doing some version of that cruder, cartoonish style he started out with. He’s only 55, so it feels like he’s got at least one more reinvention left in him…

I’d be interested to know what you think of Knights of Sidonia if you ever do end up giving it another shot, since it sounds like you and I are in a similar place with Nihei.

LikeLiked by 1 person